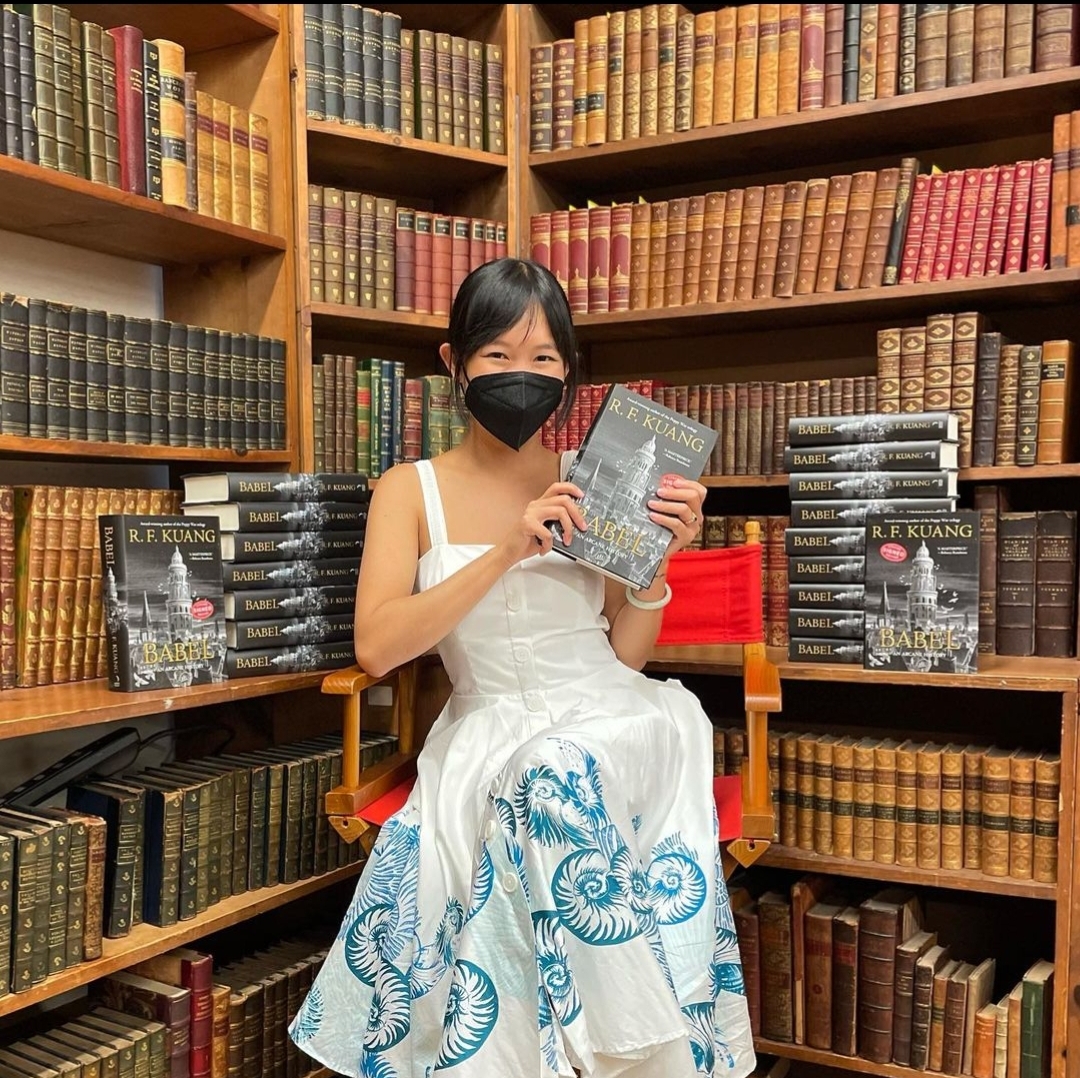

Set in the glorious and imperial London of the 1830s, the novel “Babel” by R.F. Kuang follows a young boy, Robin Swift, as he is whisked away from his childhood home in Canton by the stoic Professor Lovell. An unforgiving disciplinarian, Lovell trains Robin to master Latin, Greek, English, and Mandarin in order to prepare him for admittance into Oxford University. At Oxford, Robin forms close friendships with three of his fellow Babblers—translation scholars who study in the renowned tower of Babel, where translation is used to power magic.

However, beneath the university’s whimsical exterior lies a sinister reality: the work conducted in the prestigious tower serves Britain’s colonial endeavors and exploitation of other countries, including Robin’s homeland of China. Before long, Robin is introduced to an underground resistance that wants to overthrow the academic institution, and the novel turns to focus on his reckoning with his beliefs. At its core, the book is an allegory for how imperialist nations intellectually and materially exploit people of color for profit, and at the same time is a meta-critique of the dark academic and fantasy genres that have been widely criticized for perpetuating white supremacist ideals.

At the heart of the novel is Robin, a fleshed out and complex main character. He is caught between self-interest and integrity; he loves Oxford and wants to escape into a bubble of academia, but cannot avoid the reality that none of his actions exist without consequence. Though frustrating at times, Robin’s swings between cowardice and bravery are realistic and sympathetic, and Kuang challenges readers to put themselves in Robin’s position rather than condemn him for his mistakes.

Although Robin’s characterization is one of the book’s strongest points, that of minor characters is among its weakest. The author seldom develops character relationships with concrete examples and instead uses more patchwork, purple prose paragraphs that often ring empty. For instance, describing the main quartet of characters, Kuang writes, “By the time they’d finished their tea, they were almost in love with each other … that afternoon they could see with certainty the kind of friends they would be, and loving that vision was close enough.” The result is a cast of one-dimensional side characters that function effectively as symbolic representations in the book’s broader allegory but make it difficult for the reader to feel for them. Nevertheless, this form of character development is a staple in dark academia books (see “The Secret History”), and I can appreciate “Babel” for embodying that spirit of the genre it is critiquing.

On a different note, Kuang’s writing style is incredibly immersive. Her descriptions of Oxford’s environment and architecture are particularly phenomenal, and draw the reader into Robin’s turmoil—how can he destroy something so beautiful? Kuang’s writing secures the reader’s sympathy through all of Robin’s agony and moral ambiguity.

Finally, Kuang delivers excellent, scathing socio-political commentary and meta-critique. The magic system operates through translation: Babblers use silver to capture the essence of meaning that is lost in translation, which produces magic. They use foreign languages as a natural resource to expand Britain’s power. Not only is the concept unparalleled, but it kills in its execution. The events take place just prior to the Opium Wars—fans of Kuang’s “The Poppy War” will be familiar—and the book incorporates real historical events into the plot.

Most impressively, perhaps, Kuang practices what she preaches about confronting elitism: the book is littered with footnotes explaining translations, allusions, and historical context. In just these few strokes of her pen, Kuang transforms the characteristic pretentiousness of dark academia into something accessible and useful. She preserves the aesthetic of the genre—old books, candlelight, and homoerotic friendships—while revolutionizing its content to challenge white supremacy. Although at times the book may begin to feel like a history lesson, its fantastical elements maintain such instances few and far between.

Kuang’s central question is whether or not violence is necessary for liberation. Her answer is as nuanced, layered, and insightful as all other elements of the novel—yes, to a certain extent. Robin summarizes it poignantly, saying, “[Colonization] convinces us that the fallout from resistance is entirely our fault, that the immoral choice is resistance itself rather than the circumstances that demanded it.”