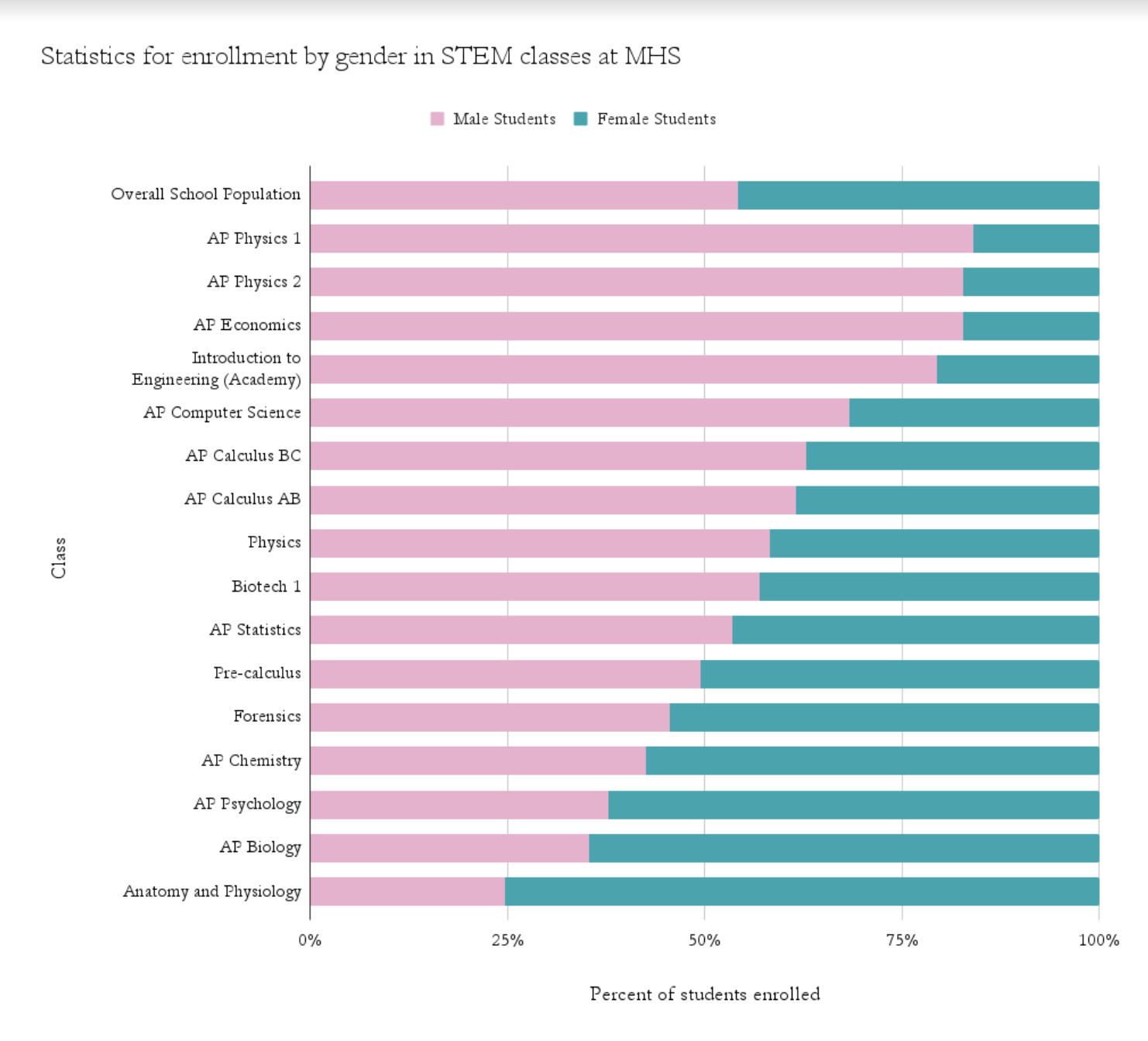

When junior Angie Wang walked into her third-period AP Physics 1 class on the first day of school, she was one of four girls in a class of 25 students, she said. According to schoolwide statistics provided by MHS staff secretary and data analyst Stacey Ryan, AP Physics 1 is one of the classes at MHS with the largest disparity in female enrollment: out of 75 students, 84% are boys and 16% are girls.

Wang noticed that AP Physics teacher Kathleen Downum had arranged for the four girls in the class to sit together, she said.

According to Downum, the seating arrangement has helped girls feel more comfortable, and she even gets requests to continue it as she plans new seating charts.

“Some of the girls will write, ‘I really appreciated having a group of girls. I’d really like to stay that way,’” Downum said. “That tells me that there is still something going on there about the comfort level and the interaction that is helping some students.”

“It might have been more difficult if there was a feeling of isolation with just me and a whole table of boys,” Wang said. “It made it more comfortable and easier to find someone to talk with.”

Girls have historically been discouraged from pursuing science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) because of a lack of role models and the perceived struggle of balancing a STEM career with the traditional household responsibilities of a woman, science teacher and Science Olympiad advisor Letta Meyer said. Meyer experienced this discrimination in her high school physics class, she said.

“I was one of two girls in my class and our teacher would literally ignore us,” Meyer said. Despite the girls having the highest grades in the class, the teacher would act as if they were incapable and did not belong there, she added.

Meyer has not noticed such overt discrimination against girls in the STEM classroom nowadays, but sometimes notices her male students dominating group discussions and attempts to prevent it, she said.

“A lot of times, our society says that the girl is not supposed to take charge,” Meyer said. “So the guys come in and take charge and just steamroll over. They don’t stop to ask, ‘What do you think? How do you think this should be?’”

Junior Brendan Tam, an AP Physics 1 student, feels that girls in his physics class are perceived and treated the same way as boys and given a “fair chance,” he said. He admires the girls for taking physics despite the significant gender gap, he added.

MHS statistics show that there is a disparity of girls in certain STEM fields like engineering, with the worst gap being in physics, but point to something very different in life science classes such as Anatomy and Physiology: there are more girls enrolled than boys.

The National Science Board found a similar trend in 2006: 81% of female scientists studied psychology, social sciences, and life sciences. Elaine Howard Ecklund, Autrey Professor of Sociology at Rice University, analyzed the cultural causes of this disparity in an article called “Why Scientists Think There Are More Women in Biology Than Physics.” She found that both female biologists and physicists perceive the discrimination against women in physics as worse than the discrimination in biology. She also found that people connect the life sciences to emotion and empathy, qualities that are stereotypically associated with women, and physics with logic and math, topics stereotypically associated with men.

However, physics can be just as people-oriented and “caring” as the life sciences, Downum said. For example, scientists use physics to design infrastructure that filters drinking water and machines to reduce the strain of manual labor, both of which have saved lives, she said.

Meyer is researching the STEM gender gap for her Ph.D., and in her investigation, she found that the Science Olympiad organization’s team-oriented approach, which encourages bonding and co-ed collaboration, has helped build confidence in girls, she said.

Wang, who is a Science Olympiad team member, agreed that Science Olympiad has helped her feel more comfortable in STEM.

“Seeing multiple captains being girls really makes me feel like I can be the same way,” Wang said.

Having such female role models is crucial to minimizing the gender gap, Meyer said. MHS is taking a step in the right direction because many of its STEM teachers, especially for AP classes, are women, she said. Other factors in the gender gap are girls’ interest in STEM, self-efficacy, performance, and competence, many of which need to be built at an early age, she added.

“Most high school students have already decided whether they hate science or not, and so, at least staying open to science for a while” is important, Meyer said.

However, the single-gender approach of separating girls and boys that some have opted for is not sustainable in the real world, where girls need to know how to collaborate with boys, she said.

Downum believes that seating girls together, at least in her introductory physics classes, is an important starting point to build “solid support” for the girls and develop their interest in physics, she said. If they choose to pursue physics, they will have a long career ahead of them to collaborate with boys, but to get there, she has to start them off in an environment they feel comfortable in, she added. Even if they are intimidated by the gender gap, girls should at least give themselves a chance to explore STEM, she said.

“You want to get the best society result; you want the best physicists,” Downum said. “It would be horrible if you’re shunting them (girls) over into something they can’t do as well, and you fail to get the brilliant stuff out. And on the personal scale, I’m just hoping that people can get to make the choices that make them the most fulfilled.”