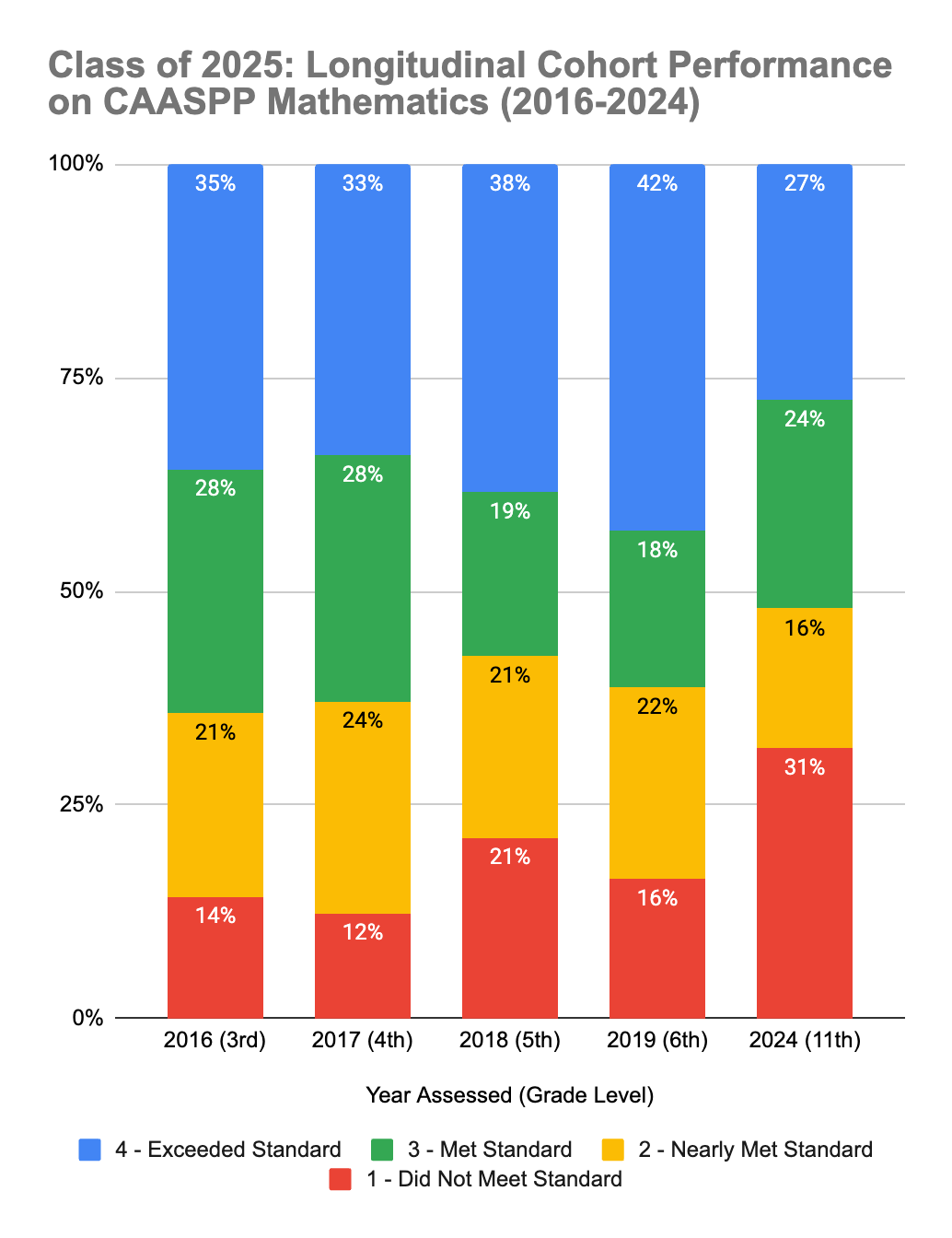

There has been a decrease in students in the class of 2025 who are meeting or exceeding the standard for the math California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP), especially from sixth grade to eleventh grade, Director of Secondary Education Maurissa Koide said at a board meeting on Oct. 8, 2024. Only about half of the class either met or exceeded the standard, according to a bar graph shown during the meeting.

When the high school principal and some of the district board members met with the dean of the School of Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Pacific (UOP), the dean shared that for the last few years, many college freshmen, who had taken accelerated math courses in high school,were not testing into the expected math level for college. , Koide said in an interview. Many of the college freshmen are placed into the pre-calculus level, Koide added.

“It has come up also with our math high school teachers that they’re seeing students struggle the more and more they accelerate,” Koide said. “The retention for the content is not always there, and so we have been having conversations around, ‘Is it helpful? Is acceleration actually benefiting students, or are we putting them on a backward path?’, inadvertently, being that we’re also hearing that now from a college partner.”

Koide would like to see, if possible, specifics on how the high school students are doing when they are entering math as freshmen in college, Koide said. Then, the district can see how they performed as seniors in high school, what math they completed, and then what math course they entered as freshmen in college, Koide said.

“That data, instead of just anecdotal statements, is important to have,” Koide said. “I also had shared that with the board, that’s kind of our next step. We’d like to hear from other colleges and see specifically how it’s impacting our students.”

Currently, the district has not found a definite correlation between college freshmen not testing into the appropriate math levels to how MHS students are performing, Koide said.

“The other thing we (the district) are looking at is our summer programming and our summer Acceleration Program, seeing, also, longitudinal data on if students are accelerating, how they (are) then faring in their high school courses once they do that,” Koide said.

There are fewer students who pass the acceleration test that self-study than those that took an actual course over the summer, Koide said. Oftentimes, the district sees that students who are self-studying are not as successful, Koide said.

“It’s hard to replace a teacher, self-studying when they have a tutor, or maybe something like Khanmigo, where they can get some tutoring support,” Koide said. “But, otherwise, it could be difficult.”

Students are required to take an actual class of Math 2, according to what UC requires, and everything else they are allowed to self-study before taking the Mathematics Diagnostic Testing Project (MDTP) test, math teacher Annie Nguyen said.

“I believe that when students self-study, they can’t self-study correctly a whole year’s worth of material in a span of six weeks,” Nguyen said. “So then, there’s a lot of gaps that are misplaced. That’s why when they go to higher level classes, or when they take an actual diagnostic class from the UCs, they are scored below what they should be.”

The gaps in the students’ skills are in their foundational skills, and they are unique to each student, Nguyen said. For example, some students can not factor in calculus, since they memorize just enough information for a test, Nguyen said.

“When they self-study, in my opinion, they don’t really know the ins and outs of all the curriculum that they’re self-studying,” Nguyen said. “They just generalize what the classes will be, and then they just study that.”

The reason why students can self-study is because when the district switched to integrated math for the high school level, not many colleges offered integrated classes, and therefore the district decided to allow students to self-study to accelerate, Nguyen said.

“They (students) had to pay thousands of dollars to be in this program, and the district felt that was an equity issue,” Nguyen said. “Not every family can afford $2,000 every summer for a student to take those courses to accelerate. So it would be unfair for those who financially can’t accelerate.”

Summer classes may provide an introductory level of understanding, but students can not be as hands-on with the skills, Tsang said.

“It’s like playing any sport,” Tsang said. “You need to have, not just the understanding part; you need to practice every day for two hours, for example, after school, to make your concept hands-on and become part of your muscle memory.”

Senior Robin Jeon took Math 2 and precalculus classes over the summer, she said. While taking the classes, the main goal was more of passing the exam at the end of the class rather than learning, she said.

“Your goal isn’t to understand what is actually behind all this, so you tend to be very negligent of what is actually going on conceptually in order to just get the problem right,” Jeon said.

The summer courses were not perfect in preparing her for the next math level, but they were good enough, Jeon said.

“It (the course) is really short,” Jeon said. “It isn’t enough to affect your results in the acceleration test, but you’ll have to probably put in a little bit more effort to master during the school year.”

Whenever the district decides to make a programmatic change, they never do so on a whim, Koide said.

“We always want to have some data to back up our decision making,” Koide said. “That’s the last thing I want to make sure is really clear to our students and our community.”