In August 2022, 18 students at Robert Randall Elementary School entered second-grade teacher Daisy Gonzalez’s classroom after over two years of learning disrupted by the pandemic, Gonzalez said. The most urgent issue was that her students were underperforming—five of them could not recognize the alphabet, and almost all of them could not add two-digit numbers, a skill they were expected to master by the end of first grade, she said.

“Right now, I’m really struggling with (teaching) reading, writing, and math because we have to fill in so many holes and gaps that they didn’t get to fill in first grade or in kindergarten because of the pandemic,” Gonzalez said.

She explained that students struggled to pay attention during distance learning, and socially-disadvantaged students often had trouble logging into her class despite district-provided Chromebooks and hotspots.

Chris Norwood, Vice President of the Milpitas Unified School District Board, agreed that chronic absenteeism was a large issue because of unstable home lives and disproportionate trauma from the pandemic, especially among special needs students, English-learner students, Latino students, and African American students.

The learning gap caused by these obstacles revealed itself in lower scores on the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) than pre-pandemic levels for certain subgroups, according to MUSD score reports. In fact, the pandemic affected students of all demographics nationwide, as the National Assessment of Educational Progress for fourth-graders showed a decline in math scores in 41 states and a decline in reading scores in 30 states.

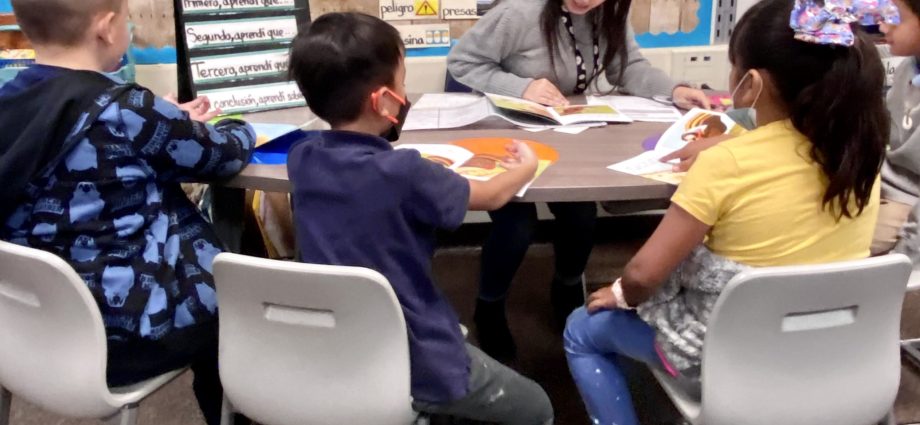

To minimize the learning gap in her classroom, Gonzalez separates her students into mathematics and reading groups by skill level, and works with each group individually at school, she said. The teachers at Randall offer intervention for students performing below grade level, with at least an hour of tutoring after school, three to four times per week, she added.

Students at Randall have benefitted from teacher-led after-school tutoring, especially with supplementary, district-funded programs like the Kids’ Club, Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) for homework help, and the Folklórico dance group that teaches dance and builds social skills, Gonzalez said. However, teachers still face an overwhelming workload to get students back on track, and high schoolers can help by volunteering, she said.

“Most of the time, I’m staying until 5 or 6 p.m., and sometimes even more,” Gonzalez said. “I have to do so many different differentiations. I have to differentiate for this student. Let me go do this activity with them or let me go print this worksheet to meet their needs. The lessons that I create have to be well-differentiated, and that differentiation takes time and work to be able to provide students with something that’s going to progress them.”

Beyond academic support, Gonzalez also said her students need help with social-emotional learning, especially when they get frustrated being unable to complete second-grade material.

This social-emotional guidance is just as important as academic support, Norwood said. The ideal tutoring program for a high schooler to start or get involved with would have both mentoring and tutoring at schools “where there’s chronic absenteeism more than not: Weller, Burnett, Randall, Rose,” he said. Students in second through tenth grade are in most need of support, he added. As someone who has tutored before, Norwood said he has seen firsthand the positive impact that these types of tutoring programs can have on students.

“The best tutors are tellers, they’re listeners, and they come alongside the learner to understand their learning style, and to deliver,” he said.

Aiming to support these learners, junior Mallika Ghante became a board member and tutor for the MHS Prepworks Club, which disbanded last year but had participation from over 70 tutors, she said. Prepworks had an untargeted approach to finding tutees, so many tutors ended up teaching new material to already advanced students, and the club failed to reach the underprivileged and below-grade-level students that needed academic help but could not afford professional tutoring, she added.

Over the summer, Ghante chartered the MHS Tutoring Academy (MHSTA) with the mission of reaching those high-needs students. To find tutees, the club contacted elementary school principals requesting that they specifically send the form to high-needs students, Ghante said. She added that the tutee sign-up form asks students to list why they need tutoring. So far, MHSTA has 15 high-needs tutees.

Considering that Prepworks had over 70 tutors last year and MHS has a 20-hour service requirement, there are likely a lot of high schoolers interested in volunteering as tutors, Ghante said. They should consider volunteering for programs like MHSTA that identify and address the community’s needs, she said.

Gonzalez agrees that high school tutors and tutoring programs should target these high-needs students to prevent the learning gap from spiraling into an achievement gap beyond college. However, she has not heard of any tutoring programs run by MHS students so far, she said. Such tutoring programs could better reach high-needs students if they directly reached out to and partnered with teachers, she added.

“Imagine yourself being in the shoes of somebody that’s below grade level—maybe you’re that type of student that was below grade level, and a teacher or your school really supported you and helped you out like we’re trying to do with our students,” Gonzalez said, addressing high school students. “Think about it that way. Maybe you can help out with this cause too.”